The Plongeur was a first for France: “an experimental vessel,” verily, “powered by a new design of atomic pile, and boasting a number of innovative design features. Its very existence was a national top secret. Accordingly, its melancholy fate went entirely unreported.” Or it did till today, half a century since its mysterious disappearance. Now, though, its story can be told. And who better than Adam Roberts to do the reporting?

West of the continental shelf, the skeleton crew of the Plongeur—the plunger, if you must—set about stress testing what was then a particularly progressive vessel. In the process, its engineers expect to identify some small problems; instead, the submarine simply sinks.

Something has obviously gone catastrophically wrong, and as the Plongeur is drawn inexorably towards the ocean floor, a collision with which is apt to collapse it—though by that depth the immense water pressure will have long since spirited away the several souls aboard—its crew of courageous countrymen prepare themselves for the inevitable: the end.

But the end did not come. Instead, and gradually, the shaking calmed, and the deep buzz of vibration quietened. It was a very long drawn out diminuendo, the noise and the shaking withdrawing itself incrementally until both had almost disappeared. Impossible to believe that the implacable wrath of the ocean was diminishing—it was against all the laws of physics.

Unbelievably, this is but the beginning of the Plongeur’s story: the end is set in what seems to be a different dimension, and it’s years ahead yet.

In the interim, as they continue to sink, the crew float (so sorry) a series of theories as to what could possibly be going on. These becoming increasingly outlandish as their situation becomes stranger and stranger still. Someone suggests they could have been sucked into a spherical channel at the very centre of the earth. Failing that, perhaps a portal has transported them to an infinite ocean; a sort of cosmos made of water. Or:

“Could it be that we have somehow slipped out of reality altogether, and into the imagination of Monsieur Jules Verne?”

The lieutenant was, of course, joking; but Jhutti, peering at the glowing end of his cigarette, appeared to be taking the idea seriously.

“A dead man’s imagination,” he said, in a dull voice. “Monsieur Lebret suggested that we had indeed all died, and were now voyaging through the unforgiving medium of human mortality. Is your idea more outrageous than his?”

It is not. Roberts keeps us guessing, however, till the fantastic last act of his latest. Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea is part pastiche, part ambitious science fiction: a hardy hybridisation which inherits some of the best elements from both the author’s normal novels as well as his semi-regular send-ups, such as the recent sequel of sorts to The Soddit.

For starters, this is a book with a brilliantly British sense of humour. Expecting to be dead in the water, as it were, the crew share certain desperate confessions. You can imagine how awkward the situation is when the “inevitable catastrophic extinction” they have prepared for simply evaporates into mystery. Meanwhile everyone smokes all the time, treating fire and flames like so much mood lighting in a highly combustible environment.

Despite said silliness, Roberts treats the greater tale with almost complete seriousness, documenting the Plongeur’s extraordinary voyage rather than making fun of its more farcical aspects. Thus “the childranha” are a source of genuine terror, and when one submariner lands on a giant hand, I too “felt a flash of panic,” if not on behalf of the character concerned.

In point of fact that’s exactly what Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea lacks. “Its captain was no-one; its crew nameless.” Those characters that there are, most of whom come and go over the course of the story, are introduced in a rushed roll call that left this reader reeling, whilst the closest thing to a protagonist we have is the observer Alain Lebret. Determined as he is “to manipulate the mood of the group,” however, he’s horrid from the offing, and if anything less sympathetic by the end. I’m afraid I tried and failed to find a single sailor to care about.

There are also some pacing problems, though the author warns us about these at least:

For three days and night the Plongeur descended. The crew passed through a period of collective elation at having escaped what had been, after all, inevitable death in that initial catastrophic descent. But this did not last long, and it was succeeded by a period of gloom. They were still alive, true; but they were confined, helpless and unable to see how, or even if, they might ever return to their homes. For twenty-four hours the captain considered whether to risk sending out a diver into the unknown waters. During that time, the depth gauge passed its limit no fewer than nine times. The crew watched with fascination, and then horror, and finally with boredom as the numbers continued their relentless accumulation.

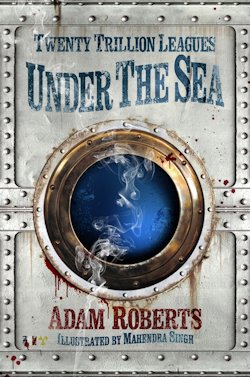

As indeed do we. Luckily, Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea is immediately appealing, and though the endless fathoms flag for a chapter or five, Roberts picks up the pace in time to pave the way for a satisfying if madcap finale, made all the more memorable by Mahendra Singh’s marvellous full page pen-and-ink illustrations.

As ever with Adam Roberts’ writing, the science is meticulous, and the fiction articulate. Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea may have more in the manner of smarts than heart, but I for one very much enjoyed the voyage.

Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea is available January 16th in the UK and May 1st in the US from Gollancz.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He’s been known to tweet, twoo.